When is an A/B test appropriate to roll out out your product feature? Opinions are split:

We built [the Mac] for ourselves. […] We weren’t going to go out and do market research.

– Steve Jobs

Prove all things; hold fast what is good

– 1 Thessalonians 5:21, New Testament, King James Bible

Read enough online advice and you’ll either end up Steve Jobs telling you to test nothing, or God telling you test everything. Choosing between God and Steve Jobs as a higher authority for tech advice is tricky.

Luckily, you won’t have to - they’re both wrong! As with most things, there is a right time and place for A/B testing. It depends.

After helping run (and not run) hundreds of A/B tests for clients, I put together a practical guide for determining whether your idea is A/B test material.

Question 1: Is your question at the right level of altitude?

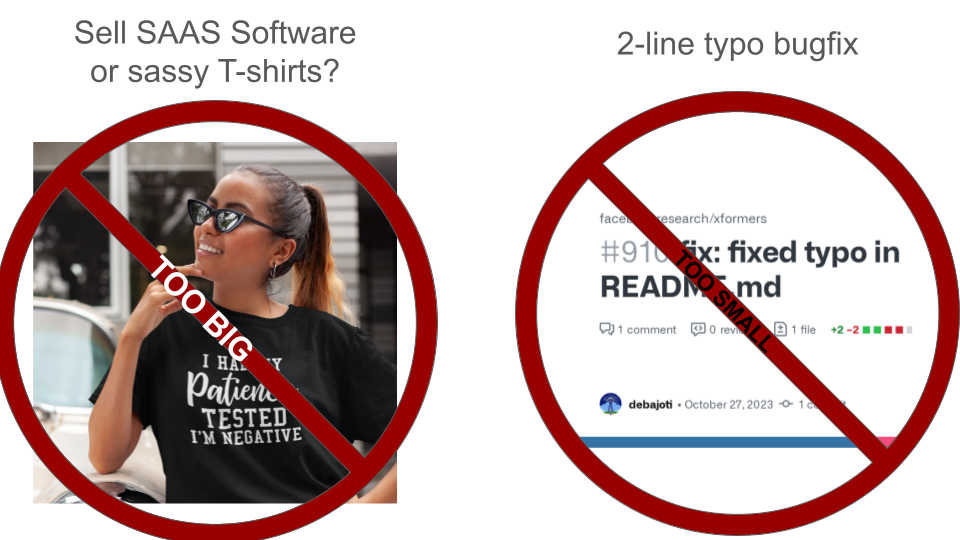

Testing is not a substitute for vision or strategy. “Should we be selling SAAS software or sassy t-shirts” is not a useful A/B test. Rely on your judgment.

Similarly, fixing a typo or other “obviously good, obviously tiny” fixes don’t need to be A/B tested. Test setup has a small but non-trivial cost. Don’t waste your time on tiny changes - just do it.

A good A/B test will help answer the “how exactly” of executing a high level strategy - IE, you know you want to sell sassy t-shirts, but should they cost $20 or $30, or should your models be male or female. The work required to get a test ready to run should take somewhere between a few days and a couple of months; any more than that, and you’re making a strategic investment and should treat it accordingly.

Question 2: Is it ready for prime time?

Back at Opendoor, I was once the engineer on the CEO’s special project to build out a completely new home-buying experience.

As a Growth guy, I naturally said “cool, run this as an A/B test to measure success.”

This was, in retrospect, a bad idea; the initial results were discouraging, and we abandoned the initiative. In truth, our approach needed more time to develop. It needed to be iterated on qualitatively first, through talking to users, getting feedback, etc, before having to compete head-to-head with the existing flow.

V1 of any new approach will do worse than V100 of an existing one. Without investing in product development, a premature A/B test will reflect level of investment, not potential.

The bigger the swing you’re taking, the more product development is warranted. Changing your Homepage CTA from “Register” to “Get Started” can be tested right away; a complete redesign of your onboarding flow merits qualitative iteration first.

A good A/B test will be comparing two or more variants that have a real shot of winning.

Question 3: Do we have the numbers?

There’s no point running a test if you don’t have enough traffic to be able to identify a winner.

Before running an A/B test, run a Power Analysis & see what level of fidelity you can measure with at your current size. You can still sometimes find ways to squeeze more significance (see my guide on the topic).

If you don’t have enough numbers to detect a reasonable win (5%) in a reasonable time period (2 weeks), don’t bother running a test - just ship the idea if it’s good or skip it if it’s risky.

A good A/B test will have a power analysis done prior to implementation, and will have an explicit finish date and minimum win size ahead of time.

Question 4: What will you do with a neutral result?

Before running an A/B test, decide whether you are running a Rollout or an Experiment.

A Rollout is an controlled release of a new feature, using a feature flag & A/B test to ensure a gradual pace and to ensure no harm is being caused by the change. Rollouts are common for infrastructural changes, core product feature releases, and brand updates, and are typically used by infrastructure or core product teams. If an A/B test result is neutral, the new feature will be released.

An Experiment, on the other hand, is an attempt to learn in order to optimize some specific business metric, and is more commonly used by Growth Engineering and Performance Marketing teams. The new variant will only be released if if an A/B test is statistically significant.

Both Rollouts and Experiments have their place, but conflating the two is dangerous. Pick one ahead of time, to avoid the “good enough” trap.

“It was so close” you rationalize. “Directionally, this is where we want to be going anyway, so we might as well ship it.” This kind of shortcut is very tempting, but will ultimately hurt your team’s ability to learn, quantify impact, and feel empowered (see below).

A good A/B test will have a written pre-commitment before starting, around whether it is a Rollout or an Experiment.

Aside: What’s wrong with shipping non-stat-sig winners?

It’s a bad idea.

1. Creates a “Participation trophy” culture

To paraphrase Aaron Sorkin, “This isn’t Growth camp. Not everybody’s experiments get to ship.”

Even great growth teams will have a win rate of under 50%. A good growth culture is one where it’s OK to have ideas that don’t win and big swings are celebrated. If we instead ship non-winners, the message you send to your team is “hey, that was close enough!”

When even mediocre ideas are good enough to ship, the team is less motivated to think big.

2. Encourages HIPPO-ism

HIPPO (Highest Paid Person’s Opinion) is a common anti-pattern for growth teams, where the boss’s ideas take precedence over their team. If you find yourself shipping a non-stat-sig winner, there’s a pretty good chance it came from the manager.

A great growth team will be organized around a data-driven meritocracy of ideas. HIPPO-ism is poison to this culture. Why bother offering your own ideas when the boss is just going to ship their own stuff, regardless of how well it does?

3. Harms a team’s ability to learn

A strong growth team builds on its own successes. Learnings from experiment winners can be elaborated on in follow-up experiments, discovering themes and levers that work across the product.

Shipping non-winners muddles those learnings. “Was X something we should build on, or just a fluke we should ignore?” If you choose to follow the questionably-winning theme, a team will run into dead ends much more often.

Quantifiable feedback is how Growth teams gain intuition and improve. Don’t poison that well.

4. Impacts a team’s ability to quantify it’s impact

Teams quantify and report their impact by tallying up the impact of experiment winners. Properly adjusted, the sum of experiment winners is a good proxy for a team’s true impact to the company.

Shipping non-stat-sig-winners raises a team’s false positive rate. This makes tallying less trustworthy: before, we knew every experiment deserved inclusion with a 95% likelihood; now, it’s more of a crapshoot.

Engineers are in demand throughout the company. Any team that can’t quantify its impact is likely to have staff distributed to teams that can provably put them to good use.

Avoiding the nightmare

Decide upfront what you’ll do if the test is not a stat-sig winner, and don’t reverse that decision, no matter how tempting.